progress update

Well, things haven’t changed much in terms of my progress toward a million. If anything, I have less money than before. I must be manifesting wrong, this isn’t supposed to work this way!

depression corner

Destiny is a funny thing. I was talking with a friend several weeks ago who described how she felt that her relationship with her husband was destined, in that when she met him, she knew that she was going to be married to him, and that she knew that disasters in their relationship would be weathered.

I don’t think that she is crazy. Maybe destiny is real. I’ve certainly never felt it. Maybe we’re fired from a canon by God, and the target is impossible to deviate from. Suppose it is real, however — there are quite a few things that are deeply unsettling that destiny entails.

First, it likely means that human life is totally meaningless to the entity or entities that weave our destinies in the great cosmic tapestry. A child that dies for no reason, a baby that gets a horrific illness, someone who is in the wrong place at the wrong moment an AC unit falls from six-stories up — all of that was determined. Unavoidable.

In The Brothers Karamazov, Ivan Karamazov gets really bent out of shape about this. His rejection of his ticket into heaven, eternal harmony that he is granted by God, is personally distasteful to him. Ivan collects newspaper clippings of horrific human behaviors, one for example being a little girl who is abused by her parents and left to die in the pit of an outhouse. And this ultimate truth, this destiny that God has ordained for us requires for us to achieve truth and harmony:

“…to me, harmony means forgiving and embracing everybody, and I don’t want anyone to suffer anymore. And if the suffering of little children is needed to complete the sum total of suffering required to pay for the truth, I don’t want that truth, and I declare in advance that all the truth in the world is not worth the price!”

If the ticket to heaven, or the ticket to peace, or the ticket to ease of mind requires such a payment, Ivan declares, “I am simply returning Him most respectfully the ticket that would entitle me to a seat.”

Though Dostoevsky himself never quite makes this argument, I think there’s something really damning in this line of reasoning and argument if you don’t accept it.

See, if we accept that things can be one way, that there is an inevitability to control and choices, and there isn’t a way to divert them. If we accept that our destiny is to grow old and fat, or live peacefully until death and the destiny of others is to simply expire, to be a footnote in the annals of history and our own narratives, then that seems to me a disgusting state of affairs. That my happiness is arbitrarily distributed, and that this distribution is outside of my control or ability, and that I ought to simply accept it, swallow the pill — that is truly a vile bit of ooze to swallow.

today in history

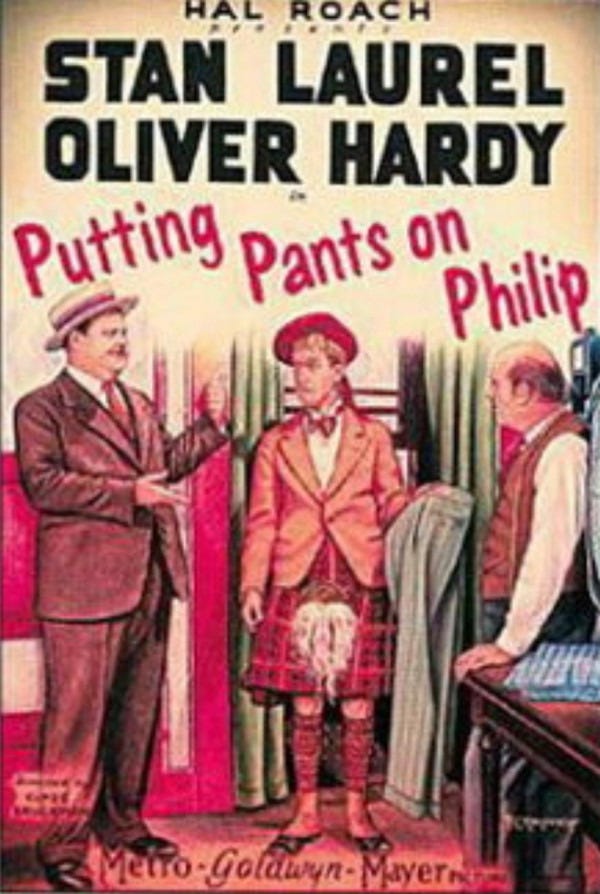

On the day of writing this, December 3rd, Laurel and Hardy’s first film, “Putting Pants on Phillip,” was released. I long for the days when the movies did what they say on the tin.

board game corner

I’ve got a new review of Inferno which just dropped that you can check out here, but this newsletter is for my Very Serious Thoughts about board games, so here goes.

For my birthday this year, I busted out one of my old favorites, Living Planet, which is far and away the most unconventional of my favorite designer, Cristophe Boelinger’s, designs.

I’ve written about it before, but the premise is this: you’ve found a planet rich in a magic mushroom that extends life and has near infinite industrial applications. Now, as good space corporations, you must harvest the mushroom, which by the end of the game will have killed the planet.

Cheery, yes?

If you’re truly a masochist, the best way to play the game is by going through a scenario generation process at the beginning. You essentially collaboratively decide what kind of planet you will have, what the victory conditions are, and alter many of the ways the game works mechanically. Collaborative might be the wrong word, because everyone gets to select an equal amount of conditions for the game, and this is where the problems start.

Everyone has a contradictory series of intuitions about how things are supposed to work. One person believes that the manipulation of someone else’s faulty memory is fair play, while another believes that this isn’t the case. Some players believe that “table talk” and negotiation about how the game is going should not ever happen, while others revel in it.

One of the most common criticisms of Living Planet is that it is underdeveloped—meaning that there are numerous situations that arise within the game that feel counterintuitive, unpleasant, or under-baked.

On my birthday play, we generated a scenario which made it impossible for players to defend themselves from the game’s disasters, allowed for networking of player resource extractors, removed private information, disallowed negotiation of any kind, removed an entire resource from play, and added an ocean that we could sail around on.

Because of the intensity and capriciousness of the game’s disasters, players immediately started linking their operations together to keep things protected from danger, or at least encourage mutually-assured destruction if it did start happening. The result was players gathering large amounts of resources, selling them on the game’s dynamic market until one player got a lead, and the bank ran out of money. At this point, the game was effectively over, and we called it to tally score.

It was not the most interesting play of the game I’ve had, and it also demonstrated the central theme of the design, which is that the game becomes a reflection of the players. One player doesn’t enjoy negotiation. I like the connection aspect of the game. One player likes boats. Another player abhors hidden information. I don’t know why one player picked the disaster thing.

The game’s scenario-based play is effectively a series of intuition pumps, or persuasion machines. Players have different opinions about what makes something fair, just, and a good game, and different mechanics tickle those intuitions. But when they all get mashed together, it’s like the game becomes a courtroom for what makes a good or interesting game. In our game it was, “who makes the most money first?” Not always my favorite idea, but it appealed to several of the players.

They deserved the boring game they got! It was my birthday!

Isn't "who makes the most money first?" the point of this newsletter? You must be manifesting wrong indeed!